On July 28, 1914, World War 1 began. The outbreak of war was met with euphoria and expectations of a quick victory that gave way to a mechanized war of frustration and attrition. From that first declaration of war to the 11th hour of November 11, 1918, war was waged predominately in Europe, with peripheral theatres throughout the world. The war caused millions of deaths and reshaped empires and colonial territories.

Carte Symbolique de l'Europe Guerre Liberatrice de 1914-1915. B . Cretee, 1914. (1).

The decade prior to 1914 saw wars of imperialism and the heightened production capabilities from the late 1800s industrial revolution. The commissioning of the Royal Navy’s Dreadnought in December 1906 and the creation of the battle cruiser class made the naval vessels of other nations obsolete. Germany, highly dependent on resources from sea trade built up its own navy in response.

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

"Follow me! Your country needs you." Elk. (2).

On June 28, 1914 while touring Sarajevo, Bosnia, Bosnian Serb nationalists assassinated the heir of the Austro-Hungarian throne,Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie. The Austro-Hungarians secured support from Germany and responded to Serbia with a forty-eight hour ultimatum. Serbia shocked the world by agreeing to almost all of the terms.

Nearly a month later, Russia partial mobilized their soldiers to aid Serbia. Despite Serbia’s near total compliance, on July 28th Austria simultaneously declared war on Serbia and bombarded their capital. This attack sparked the simmering tensions. Within a week, German had declared war on Russia, France, and Belgium. Each of these countries responded in turn, and the United Kingdom joined in to protect Belgium. At this point, the United States chose to remain neutral.

"One of the pathetic farewell scenes when "Armageddon." Juniata Echo, October 1914. (3)

the 85th went away last night",Montreal

Daily Star, p.1, 21 August 1914. (4).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

By 1915 the fighting in Western Europe had settled into a stalemate and Germany and Britain attempted to interrupt trade with their naval forces. Prior to this, the United States benefited through trade with both warring parties, but disproportionately financed the Allied war effort. The British navy established a naval blockade and Germany used U-boats (submarines) to sink any vessel approaching the United Kingdom. While both naval strategies disrupted United States trade, the German strategy caused greater agitation as it resulted in the loss of American lives.

"Take Up the Sword of Justice." B. P. (5). Note the sinking Lusitania in the background.

Cover of the sheet music for Alfred Byron's "I didn't raise my boy to be a soldier. "(6).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

"I want you for the U.S. Army." James Montgomery Flagg (7).

While a “preparedness” movement had been active within the United States prior to 1914, the US was still largely unprepared for war. Because of insufficient volunteers, the United States government chose to raise their army through conscription. All men of applicable age were required to register.

Congress passed the Espionage Act in June 1917, initially to prohibit interference with military recruitment. In practice it was used to silence dissenting voices, particularly socialists.

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

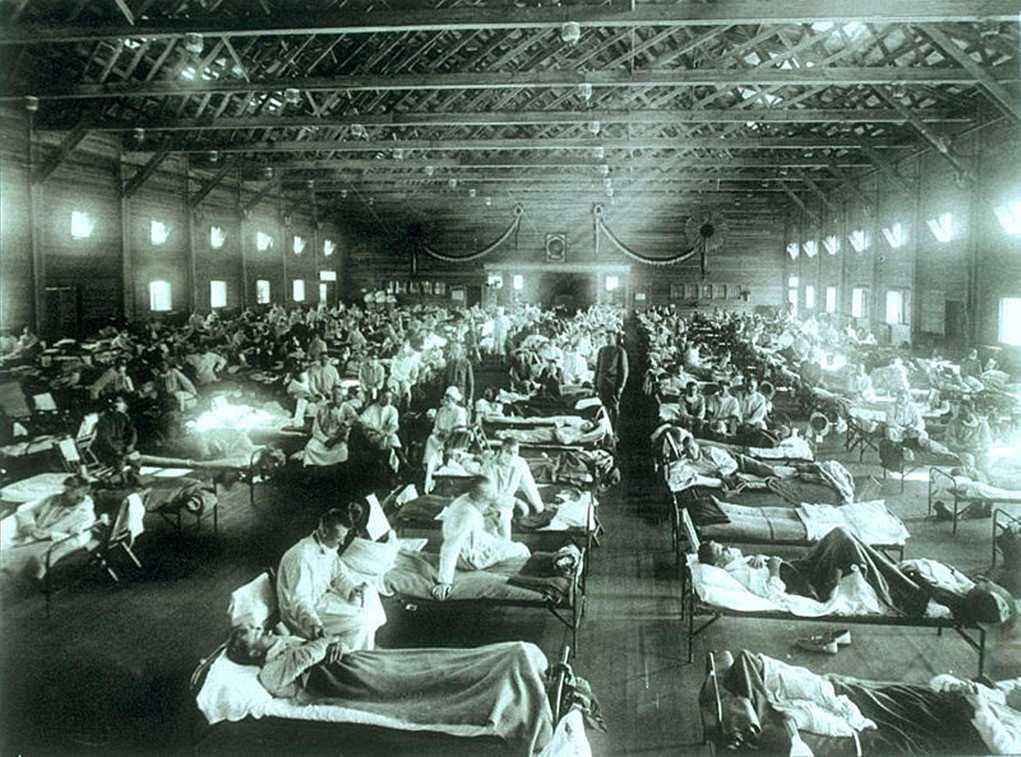

From March 1918 to November 1919, influenza killed over 50 million people globally. The first wave, while mostly non-lethal, caused great disruption in daily lives of both soldiers and civilians. It was given the name “Spanish” flu due to news from Spain not being censored because it was a neutral country.

"Emergency Military Hospital." Camp Fuston, KS. (10).

"Influenza Ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Wash D.C." Harris & Ewing, 1918. (11).

A more infectious virus appeared in March, 1918 and spread to two large US military camps and from there  spread rapidly, following the routes of troop movements.

spread rapidly, following the routes of troop movements.

In August 1918 the virus mutated again becoming much more lethal.

It penetrated deep into the lungs, causing pneumonia and other complications. Those affected suffered high fevers, racking coughs, foul odors, or trouble breathing.

Advertisement for Peruna from Huntingdon Semi-Weekly News. October 1918. (12).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

October opened with a continuation of the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Kaiser Wilhelm appointed Prince Maximilian as Chancellor of Germany, who formed a new government and sued for peace. Both the German and Austro-Hungarian armies were severely weakening due a combination of illness, war-weariness and starvation. By the end of the month the Austro-Hungarian armies were refusing to fight, marching to the rear or mutinying, while the state itself was coming apart into separate nations.

October opened with a continuation of the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Kaiser Wilhelm appointed Prince Maximilian as Chancellor of Germany, who formed a new government and sued for peace. Both the German and Austro-Hungarian armies were severely weakening due a combination of illness, war-weariness and starvation. By the end of the month the Austro-Hungarian armies were refusing to fight, marching to the rear or mutinying, while the state itself was coming apart into separate nations.

Advertisement for Liberty Loan War Train, Loan Campaign October 1918. (15).

In Huntingdon, PA, a special Liberty Day was planned for November 12th to encourage the purchase of war bonds. During the event, several thousand people viewed war trophies carried by the liberty loan train and heard speakers representing various allied armies. Later that week, influenza struck Huntingdon, leading to the closure of Juniata College on October 14.

"Death's Great Harvest." Huntingdon Globe, October 24, 1918. Pg 3. (13).

"What is your share?" Advertisement for the Fourth

Liberty Loan Campaign October 1918. (14).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

"Peace Hurrah."New York City. (16).

Following a sailor’s revolt at the end of October and early November, Germany descended into civil war. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated, and a new government was formed as the Republic of Germany. An armistice was signed and took effect at 11 am on November 11, 1918. On the off chance the armistice failed, the Allies advanced to the most favorable positions until 11 am. These actions caused thousands of casualties on the last day of the war.

“The war is over.” News of the armistice spread and was met with rejoicing by the allies. Word reached Huntingdon at 3:30 am Monday November 11 as the “whistles at the car shops sounded the first notes of the glad tidings and later the fire and church bells chimed in.” A parade was immediately planned for 7:30 pm that drew several thousand people. By this time, influenza had run its course in Huntingdon and Juniata College reopened.

“The war is over.” News of the armistice spread and was met with rejoicing by the allies. Word reached Huntingdon at 3:30 am Monday November 11 as the “whistles at the car shops sounded the first notes of the glad tidings and later the fire and church bells chimed in.” A parade was immediately planned for 7:30 pm that drew several thousand people. By this time, influenza had run its course in Huntingdon and Juniata College reopened.

Hear the war end through the Imperial War Museum and Codat to Coda.

News of the Armistice from the Huntingdon Semi-Weekly News November 11, 1918. (17).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

"The unveiling ceremony on 11 November 1920." Horace Nichols. (18).

World War I was touted as the “war to end all wars,” but instead served as the catalyst for many more conflicts. Prior to the outbreak of the war, Europe was largely led by monarchs. By the end of the war many of those monarchs were deposed or their power significantly weakened.

The Allied powers met in Paris in 1919 for peace talks and to draft what would become the Treaty of Versailles. This treaty was presented as a dictated a peace to Germany.

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles 1919." William Orpen, 1919. (19).

As the First World War Centenary comes to a close, it is both a time to reflect on the effect, nature and meaning of war as well as the meaning of peace. As George Santayana is attributed to having said: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

"Poppies." E. T. Fisher, 1886. (20).

Read more about this topic from these featured books from our circulating collection. Not on campus? Click the title of the book to find it at a library near using Worldcat.

Francis Reynolds and C.. W. Taylor. Collier's photographic history of the European War. Including sketches and drawings made on the battle field. 1917. https://archive.org/details/collierquotspho00reyn

Berliner illustrierte Zeitung October 31, 1915 No. 44. Available online from the French National Library https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1176478j.item

Full Citations for Images Featured on Posters

1. B. Crétée. Carte Symbolique de l’Europe Guerre Libératrice de 1914-1915. 1914. Hand Colored Lithograph. 48 x 57 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647864/

2. Elk. Follow me! Your country needs you. 1914. Color Lithograph. 73 x 49 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003662920/

3. “Editorial: Armageddon.” Juniata Echo. October 1914.

4. J. A. Millar. One of the Pathetic Farewell scenes when the 85th went away last night. 1914. Photograph. University of Victoria Library. Victoria, Canada. https://www.flickr.com/photos/128520551@N04/19345678448

5. B. P. Take up the sword of justice. 1915. Color Lithograph. 102 x 63 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003675668/

6. Leo Feist. I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier. 1915. Score. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002600251/

7. James Montgomery Flagg. I want you for U.S. Army: nearest recruiting station. 1917. Color Lithograph. 102.3 x 75.5 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/96507165/

8. U. S. Marines in France Digging In. Training for modern warfare consist mostly in digging one trench after another, and our boys, realizing the importance of this training, go at it with a will. 1917. Photograph. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013649103/

9. U.S. soldier & Canadian “Kiltie.” 1917. Glass Negative. 12.7 x 17.78 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ggbain.24901/

10. Emergency military hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas, United States. 1918. Photograph. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces, Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. United States. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spanish_flu_hospital.png

11. Harris & Ewing. Influenza ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Wash., D.C. [Nurse taking patient’s pulse]. 1918. Photograph. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016648028/

12. “Peruna.” Huntingdon Semi-Weekly News. October 28, 1918.

13. “Death’s Great Harvest.” Huntingdon Globe. October 24, 1918.

14. “What is your share?” Bucks County Gazette. October 11, 1918.

15. Coming, Victory Liberty Loan war train. 1918. Color Lithograph. 96 x 46 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003652834/

16. Peace Hurrah. 1918. Glass negative. 12.7 x 17.78 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014707906/

17. “Armistice Signed at 2:45 this Morning – The War is Over.” Huntingdon Semi-Weekly News. November 11, 1918.

18. Horace Nicholls. Unveiling of the Whitehall Cenotaph. The Graphic. November 20, 1920. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cenotaph,_Whitehall#/media/File:Cenotaph_Unveiling,_1920.jpg

19. William Orpen. The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles 1919. 1919. Oil on Canvas. 152. 4 x 127 cm. Imperial War Museum, London, United Kingdom. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/20780

20. E. T. Fisher. [Poppies]. 1886. Chromolithograph. 36.1 x 25.8 cm. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003664050/

Sources Consulted to prepare this display:

1914- 1918 - Online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War as a whole was very useful, in particular the entries listed below.

Brose, Eric: Arms Race prior to 1914, Armament Policy , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10219.

Hall, Richard C.: War in the Balkans (Version 1.1), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2018-04-04. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10163/1.1.

Keene, Jennifer D.: United States of America , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10045.

Mombauer, Annika: July Crisis 1914 (Version 1.1), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2018-09-20. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11027/1.1.

Medlock, Chelsea Autumn: Lusitania, Sinking of , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10051.

Mulligan, William: The Historiography of the Origins of the First World War , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-11-30. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11016.

Phillips, Howard: Influenza Pandemic , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10148.

Tunstall, Graydon A.: The Military Collapse of the Central Powers , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-04-30. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10633.

Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: The Way to War , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10152.

Yockelson, Mitchell: Pre-war Military Planning (USA) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10340.